![Vordan Karmir - Armenian kermes crimson dye]()

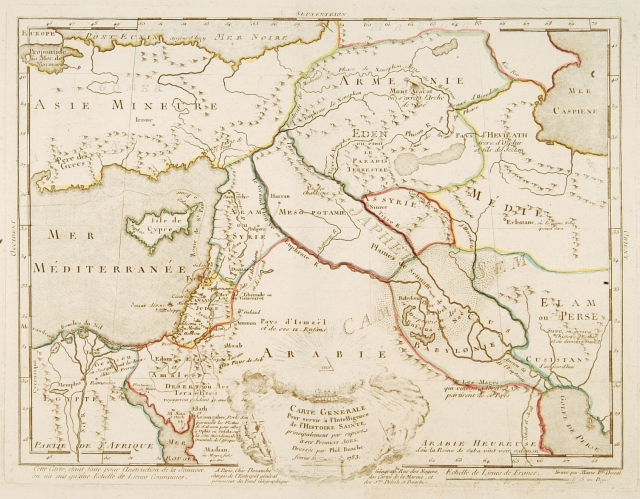

The color that once mesmerized the old world, extracted from an insect known to Europeans as Kermes and Kirmiz to the Arabs, has its roots in the Armenian Ararat valley. It is the ancient symbol of power and admiration, essence of beauty and goodness. The lowly scale bug, lies at the center of the creation of one of the most rare and special pigments known to man. The secret of the preparation of the truly permanent dye, one which defies the destructive forces of light, temperature, humidity and time, was kept by our Armenian ancestors for over 2,000 years, passing it down from generation to generation. Tragically, the secret was lost only 100 years ago as artificial dyes gained broader acceptance among consumers. Seven colors, ranging from dark-blue through blackberry to Jaffa-orange have been extracted but one yet remains illusive. The missing tone is the same shade of truest crimson that made “Araratean cochineal” famous throughout the world.

The loss of the wonder of the orient

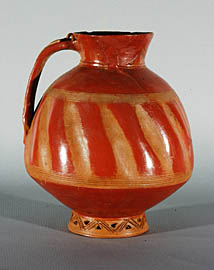

The dye has been prepared in the Ararat Valley since the most ancient times. The Bible mentions that Noah’s descendants wore garments colored with a red dye made from the scale bug. Records of Sargon II that dated to 714 BC make note of the precious crimson fabrics had been taken from the country around Ararat as trophies of war. The dye extracted from the adult insects was used by the kings and high priests alike to seal their most important documents. Ancient physicians also took advantage its medicinal qualities: soothing temperatures, antiseptic for wounds, and for contraception. The textiles made with Armenian crimson were highly valued in Greece and Rome alike. The beauty queens of the time had many cosmetic uses for the bug. Additional recognition came during the Arab invasion in the period of 7th to 9th centuries AD, when the Europeans declared it the “Wonder of the Orient” for its unique ability to delight the eye.

Some of the more specific descriptions of the dye and the bug are to be found in the notes of Arab travelers and explorers. A renowned writer and geographer, Abu-Isaak Al-Istarkhi, mentioned in his book the Roadmap of Kingdoms (930 AD):

“In the city of Dabil (Dvin) woolen dresses, carpets, pillows, saddles, ropes and many other articles of Armenian industry are made. Also, the red dye kirmiz is manufactured here, and it is used to dye fabrics. I discovered that kirmiz is extracted from the larvae that knit around themselves just as silkworms do.”

Another Arab traveler, Shams Ud-Din Al-Muqaddas, reports:

“Kirmis… is a worm that lives in the ground; women go there and collect the worms in copper… Which they later place in bread ovens.”

In the period of the 9th through the 11th centuries AD, Armenians were active in international commerce. Dvin was an important transit destination on many trade routes. One of the essential exports was crimson. Armenian carpets made of red wool were very much in fashion in ancient times. Judging from the high value of Vordan, its manufacture surely generated great returns and naturally the dye trade flourished. In addition to Dvin, Artashat was also known for its dyes. Form the 7th to the 13th centuries there were so many dye manufacturers in the city that it was often called Kirmiz.

From a much later period, there is evidence that Stradivarius and Leonardo Da Vinci used Armenian crimson, and that Rembrandt tried to acquire the vordan as well. With Columbus’s discovery of the Americas, Vordan Karmir had to give way to its crimson cousin, the South American cochineal. Brought from the New World, the new bug received wide popularity for its ease of use in production and availability. That said, its qualities were no match for vordan’s, but the immigrant bug became more and more widely used. The Armenians of the time may also have erred in failing to guard the production secrets used for the new bug as closely as they had the old.

The underground life of the Araratean chochineal

The life of the red scale bug is also tangled in mystery. They spend most of their days up to 5 centimeters below the ground, feeding on the roots of a plant called Vordan. They come out to the surface only during their mating season, in the months of September and October, that lasts about 40 days. The males and females are distinctly different. Only the females are used for extracting the pigment; they are bigger than the males and have an oval shape. After conception, the females return to the underground where they lay their eggs. Accomplishing this important mission, the adult females soon die. To observe the creatures in their natural habitat, you have to travel to the grasslands of the Ararat valley on a early Autumn morning. You won’t miss the bright puddles of congregating crimson specks. The locals claim that in the old days there was so much of Vordan Karmir that they made the entire valley look like it was covered with a crimson carpet.

Search for the lost recipe

Researchers managed to extract that very crimson color, referred to as “tzirani” (apricot) in the manuscripts, but they are having trouble keeping it fixed. The dye changes its tone rapidly. Nevertheless, the search for the ancient recipe continues in Matenadaran. A great hope is laid upon experiments with the roots of the plant Lotur, as many ancient authors claimed that it aids the brightness of the desired crimson tone.

For a time, the scientists were puzzled by the fat reserves of the insect. Constituting 30% of the insect’s overall body weight, it was getting in the way of acquiring the pigment, which is only 2-5%. However, the problems associated with the excess fat was resolved in Matenadaran. They learned to separate it during the boiling process, the same way as glycerol was collected during the preparation of soap. One of the recipes, written in 1830 by the Archimandrite of the Echmiadzin monastery Isaac Ter-Grigorian, dictates: “After the insects are mortified in the solution by potassium carbonate, they shall be kept in water for 24 hours. Then boil it in saponaria solution, add lytrhum and alum. Then filter and dry.”

In addition to the insect itself, the compound also includes hedgehog fat, ant eggs and other rarities. However, perhaps the most important ingredient of the mysterious dye is the prayer which is to be recited during the process of preparation, at least three times. “Ancient manuscripts give us clues that would be impossible to decode without knowledge of the Holy Scripture. Generally speaking, our forefathers would not start any project without a prayer,” declared Armen Saakian, who has been serving as a deacon (sargavak) in one of the churches in Yerevan since 1993. In the exhibition halls of Matenadaran one can enjoy the finely crafted manuscripts of the ancient masters. The images have preserved their original freshness, despite the fact that many of them were abused or kept in unfavorable conditions. Saving the books from frequent enemy attacks, Armenians immured them into the walls or buried them in the ground. Nevertheless, neither the damp of the monasteries, nor the hostile environment of the soil, managed to extinguish the crimson fire of Vordan.

Actually, the creature is not only instrumental in preserving the crimson of the manuscripts. It is also famed for having intense rejuvenating effects on human skin. Armen Saakian has spent over a decade on recreating the recipe for a skin ointment. Today the mildly pink “Vordan Karmir” cream is on the market to help those in pursuit of preserving their youth. It has amazingly efficient antioxidant, with moisturizing, purifying and antiseptic qualities. In medieval Armenia, only the ladies of the nobility could take advantage of Vordan, but now through the efforts of Armen Saakian and others, it is somewhat more accessible. The magic cream has already gained recognition in Europe and Russia. In the words of Saakian, “All that we have accomplished in our Institute so far is just a drop in the ocean. The manuscripts of Matenadaran contain many more secrets yet to be discovered.”

Source: Gayane Mirzoyan - Yerevan Magazine, Winter, N3, 2008

![]()

![]()